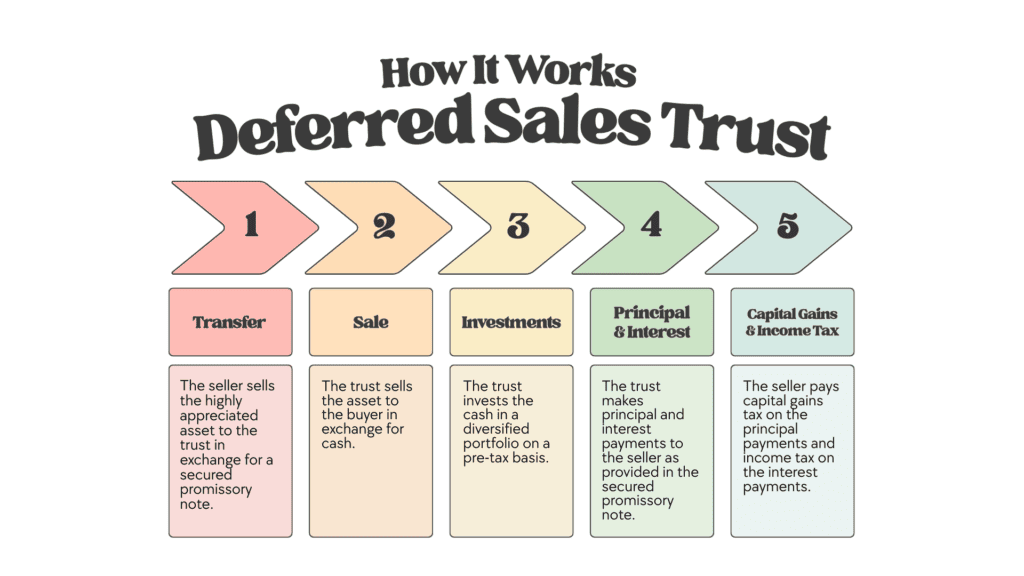

Deferred Sales Trust

A deferred sales trust is a tax deferral strategy that allows sellers of highly appreciated assets (like a closely-held businesses) to defer capital gains tax over several years.

Pros & Cons of a Deferred Sales Trust

Pros

Tax Deferral: Spreads out capital gains taxes over time.

Flexibility: The seller can diversify the proceeds into various investments (private equity, real estate, public equities, etc.).

Income Stream: Provides a flexible, predictable stream of passive income.

Estate Planning: Can be structured to transfer wealth and protect wealth.

Cons

Complexity & Cost: Involves significant setup fees and ongoing management costs (legal, trustee, investment fees).

IRS Scrutiny: The transaction has a higher risk profile than a standard sale.

Reduced Liquidity: The seller gives up immediate access to the lump sum of cash and is locked into the installment schedule.

Loss of Control: The seller must relinquish full control of the asset and its proceeds to an independent trustee.

Income Tax Analysis

Pre-1980 Precedent

An installment sale involving a related party consists of three distinct parties: the taxpayer (seller), the related party purchaser (related party), and an independent third-party purchaser (purchaser). Such transactions also involve at least two sales: the original installment sale by the seller to the related party, and a cash resale by the related party to the purchaser usually in the same year as the original installment sale.

Prior to 1980, Section 453 provided that income from installments sales could be reported under the installment method but did not explicitly disallow installment sales between related parties. Accordingly, the Service litigated several cases over the issue of the legitimacy of an installment sale to a related party. The Service relied primarily upon the doctrines of constructive receipt and substance over form when attacking the legitimacy of an installment sales to a related party. Neither the courts nor the Service applied these two theories with any degree of consistency, which resulted in significant taxpayer wins in court and inconsistent precedent. In 1980, Congress made changes to Section 453 (discussed below) to end perceived abuses of installment sales to related parties. The significant pre-1980 precedent is discussed here.

Revenue Ruling 73-157

The classic example of this form of installment sale is found in Revenue Ruling 73-157. The ruling outlines two situations: an installment sale by a father to his son, and a similar installment sale by a taxpayer to his controlled corporation. In both situations, the son and the corporation resold the property to a third-party pursuant to a prearranged plan of resale between the taxpayer and the third party. The Service denied both taxpayers the benefits of Section 453 on the ground that both transactions lacked economic reality. The taxpayer’s son and the controlled corporation were deemed to have served merely as agents or conduits for consummation of the taxpayer’s prearranged resale.

Revenue Ruling 73-536

In Revenue Ruling 73-536, the ruling involved an installment sale of securities by a wife to her husband. The parties intended that the husband would immediately resell the securities to finance his own purchase of them. A resale did not occur, however, until four months after the original installment sale. Citing Revenue Ruling 73-157, the Service ruled that the mere intention of, or understanding between, the original parties that the related party would resell the property was to be considered as “strong evidence that the original sale lacked economic substance.” As in the first situation discussed in Revenue Ruling 73-157, the Service concluded that the husband had acted merely as an agent or conduit for his wife in selling the property, emphasizing such factors as the relationship of the parties and their knowledge of the husband’s intent to resell.

Revenue Ruling 77-414

In Revenue Ruling 77-414, the taxpayer desired to sell the development rights to his property to a local county board. He sought to report the transaction under Section 453, but local law prohibited the board from purchasing property on the installment method. Therefore, the county interposed an independent, third-party bank between itself and the taxpayer. Pursuant to a prearranged plan, the taxpayer sold the development right to the bank under the installment method, and the bank immediately conveyed the right to the county for a lump-sum payment. Citing Revenue Ruling 73-157, the Service concluded that the bank was an “unnecessary” intermediary. In support of this conclusion, the Service cited the Tax Court decision in Wrenn v. Commissioner.

Wrenn v. Commissioner

Wrenn involved an installment sale of stock by a husband to his wife. Mrs. Wrenn resold the stock on the same day and, pursuant to the original sales agreement, purchased mutual fund shares as security for her installment obligations. The Commissioner contended that the entire transaction lacked a business purpose, identifying such factors as the intrafamily nature of the sale, the prearranged resale, and the retention of the proceeds within the family unit. The Tax Court held that while interspousal sales are subject to close scrutiny, they do not per se create an agency relationship. The Tax Court determined that the legitimacy of an intrafamily installment sale should be tested by the degree of independence of the parties and the presence of a substantive, if not a business, purpose. In light of the marital relationship of the parties, the intended resale of the property by the related party, and the lack of any substantive purpose for the original installment sale, the Tax Court concluded that the taxpayer failed to carry his burden of proof.

Rushing v. Commissioner

The most famous of the installment sales cases involving a sale to a trust of stock in a corporation liquidating under Section 337 is Rushing v. Commissioner. Rushing involved a taxpayer who was one of two coequal owners of two corporations. In 1962, the corporations adopted Section 337 plans of liquidation. Thereafter, all the assets of the corporations were sold. Just prior to the expiration of the statutory twelve-month period within which the corporations were required to liquidate, the taxpayer sold his shares in the liquidating corporations on the installment basis to a newly-formed, irrevocable trust.

In an attempt to deny the taxpayer, the benefits of Section 453, the Commissioner raised such arguments as assignment of income, agency/conduit, and constructive receipt. The court rejected all three contentions. In the opinion of the court, the assignment of income concept addressed the issue of which taxpayer was the proper taxable party. The court noted that in Rushing there was no question whether the seller would eventually recognize the full amount of his gain; the only real issue was one of timing. Under such circumstances, the court could not find any grounds for invoking the assignment of income doctrine. Turning to the constructive receipt and agency arguments, the court stated the test as follows: “In order to receive any installment benefits the seller may not directly or indirectly have control over the proceeds or possess the economic benefits therefrom.” Applying this test, the court emphasized the following factors:

1) the trust was an autonomous Corporation that was irrevocable and independent of the taxpayer’s control; the trust was neither a puppet nor an “economic serf” of the taxpayer;

2) the taxpayer retained no control over the liquidating distribution; and

3) the trustee had independent duties and responsibilities to persons other than the taxpayer.

Relying on these factors, the court held the Section 453 sale to be bona fide.

Weaver v. Commissioner

Rushing was affirmed in Weaver v. Commissioner. In Weaver, the taxpayer, and his brother each owned fifty percent of the stock of Columbia Match Co. (“CMC”). After completing negotiations for the sale of all of the corporate assets, the taxpayer, and his brother each created irrevocable trusts for their children and sold their CMC stock on the installment method to the trust. Immediately thereafter, the bank, as trustee, adopted a Section 337 plan of liquidation, liquidated the corporation, and transferred the assets to the purchaser.

The Service attacked this arrangement on numerous grounds: lack of economic reality, agency/conduit, and substance over form. In a detailed opinion, the court rejected all of these arguments and held for the taxpayer. The decision in Weaver rests squarely on the two-part, control or economic benefit test of Rushing. The court observed that in Rushing the sale had economic substance because the trustee had the power to void the plan of liquidation. In Weaver, as in Rushing, the trust was irrevocable, the trustee was independent of the taxpayer, and the trustee owed fiduciary responsibilities to the beneficiaries (of which the taxpayer was not one). Despite the presence of a prearranged, informal understanding between the seller and the trust that the trust would resell the assets, the trustee was under no obligation to do so. The trustee’s sole legal duty was to act independently to protect the interests of the beneficiaries. Examining specific prohibitions in the trust agreement regarding invasions of principal, the court determined that none of the limitations were unfavorable to the trust or designed to prevent the possibility of an appreciating corpus. Such factors as the taxpayer’s lack of control over trust investments, the absence of any collateral for the trust’s installment obligations, and the risk of corpus appreciation or depreciation inherent in the trust’s investment policies, distinguished this arrangement from the line of unfavorable escrow cases. The court observed that two issues of control inhered in the Weaver arrangement: the trust’s control over the liquidation, and the taxpayer’s control over the trust. The absence of the latter of these two factors was found to be determinative of the Service’s substance over form argument.

The Weaver court concluded by outlining three factors crucial to its decision in favor of the taxpayer:

1) the taxpayer exercised no direct or indirect control over the trust – the trusts were independent and did not serve as mere conduits for the taxpayer;

2) recovery of the taxpayer’s investment was limited solely to the trust’s installment obligations; and

3) the trust bore significant economic risks of corpus appreciation or depreciation.

Pityo v. Commissioner

In Pityo v. Commissioner a taxpayer created five irrevocable trusts for his children, gave $100,000 to the trusts, and, on the same day, sold $1,032,000 worth of stock to the trusts on the installment basis. Prior to the sale, the taxpayer was advised that the stock should be sold and reinvested in mutual funds. The trustee agreed with such a plan, and the parties expressly indicated their intent that the proceeds be reinvested accordingly. Similar to theories proffered in Rushing and Weaver, the Commissioner again raised the constructive receipt, agency/conduit, and substance over form arguments.

Once again, the court found the control or economic benefit test of Rushing to be determinative. As in Weaver and Rushing, the court emphasized that the trust was an independent Corporation with fiduciary obligations to its beneficiaries. The court distinguished Revenue Ruling 73-157 on the grounds that a prearranged resale was absent. In that ruling, the installment sale was made only after a prearranged sale with the ultimate purchaser had been negotiated. In contrast, the Pityo trust was under no obligation to resell. Although the taxpayer expected the trusts to resell the stock, the trustee was under no obligation to do so. Like the Weaver court, the Pityo court observed that the trust bore significant risk of potential future gain or loss. At all times, however, its duty of exclusive allegiance to the beneficiaries, not the settlor, was controlling. Therefore, the trustee’s prior, informal understanding with the taxpayer that it would resell the shares was deemed not to be determinative. Finally, the court addressed the issue of substantive purpose, a concern first raised in the Wrenn decision. The court experienced little difficulty concluding that the trustee’s independence, the economic risk it bore with respect to corpus appreciation or depreciation, and its fiduciary duties to the trust beneficiaries created numerous substantive purposes for the structure of the transaction both from the perspective of the trust as well as the taxpayer.

Roberts v. Commissioner

Pityo was cited with approval in Roberts v. Commissioner. On facts nearly identical to those of Pityo, the Commissioner raised the same arguments and was unsuccessful again. As in Pityo, satisfaction of the Rushing test was at the core of the controversy. The Commissioner objected to the use of the Rushing control test in a case involving a trust used to effectuate an open-market sale. The court, however, observed that the primary purpose of the Rushing test, determination of the independent significance of the intermediary, was the exact issue in controversy. In the words of the court, if the intermediary is an independent Corporation, “[the fact that the [taxpayer] may have opted …to put the proceeds beyond his legal control does not vitiate …the transaction once it was consummated.” Turning to the issue of the independent significance of the trust, the court identified various factors relevant to the inquiry.

1) The court observed, the trust was irrevocable and was a valid and distinct Corporation under state law;

2) Despite the fact that family trustees were used, the court accepted the taxpayer’s evidence concerning their economic independence;

3) By possessing the sole authority over whether the stock should be sold and, if so, when it should be sold, the trustees were under no obligation to resell the stock. The mere fact that a resale was intended by the parties did not destroy the legitimacy of the original installment sale; and

4) The court noted, the absence of any security for the trust’s obligations left the seller as a “party at risk.”‘

Based upon these facts, the court recognized the transaction as a legitimate installment sale.

Nye v. United States

An intrafamily installment sale was recognized as bona fide in Nye v. United. As in Wrenn, one spouse sold securities on the installment method to the other spouse. The taxpayer was aware of her husband’s intention immediately to resell the securities in order to liquidate his own business liabilities. Citing Revenue Ruling 73-157, the Commissioner contended that the marital relationship of the parties placed the purchasing spouse in the position of an agent or conduit for the selling spouse. Based on Rushing v. Commissioner, the court concluded that the proper test for determining the legitimacy of an intrafamily installment sale was whether the seller directly or indirectly controlled the proceeds of the resale or derived any economic benefit from the transaction. The court rejected the Service’s contention that the mere fact the seller was aware of the related party’s intent to resell precluded the seller from reporting her gain on the installment method. In addition, the court denied that the marital relationship of the parties, standing alone, was determinative of the issue. Although such a relationship might give rise to a presumption of agency, the court observed that the unique factual setting of the transaction rebutted any such presumption. Pointing to the economic independence of each spouse, the sizeable personal estate of each, and the absence of any apparent control by the wife over the resale proceeds, the court rejected the Service’s analogy to Revenue Ruling 73-157.

Installment Sales Revision Act of 1980

On October 19, 1980, President Carter signed into law the “Installment Sales Revision Act of 1980” (“Act”). Section 453(e) was enacted in the Act. The Senate report accompanying the Act explains that Section 453(e) was enacted as a response to the use by taxpayers of installment sales to a related intermediary in order to defer recognition of gain while at the same time effectively realizing appreciation on the property by means of a resale to a party outside the “related group” for an immediate payment. The perceived abuse exists because the original seller defers the recognition of gain through the use of the installment method; however, the resale by the related party results in realization of the appreciation without recognition of the attributable taxable gain. This is because the related party obtains a cost basis that includes the amount of the installment obligation. Therefore, the related party will recognize only the fluctuation in value occurring after the installment purchase.

Moreover, the seller may achieve some estate planning benefits since the value of the installment obligation generally will be frozen for estate tax purposes. Any subsequent appreciation in value of the property sold would not affect the seller’s gross estate since the value of the property is no longer included in the seller’s gross estate.

The Senate report explains the provision as “an acceleration of recognition of the installment gain from the first sale…to the extent additional cash and other property flows into the related group as a result of a second disposition of the property.”

The Senate report discussed the case law outlined above. The Senate committee noted that this problem had been an issue in a variety of related-party contexts, including situations in which the intermediary was a family member.

The legislative history indicates that Congress believed “that the application of the judicial decisions, involving corporate liquidations, to intra-family transfers of appreciated property has led to unwarranted tax avoidance by allowing the realization of appreciation within a related group without the current payment of income tax.” Cases where installment treatment was allowed for stock that was sold to a related buyer and then liquidated, as in Rushing, plainly were among those whose result Section 453(e) was designed to reverse. Treating a liquidation of the stock by a related party as a disposition, therefore, comports with the language and legislative intent of Section 453(e).

Section 453(e)

Generally, gain from the sale of property is taxed to the seller in the year of the sale. However, Section 453 provides an exception to this rule, allowing income from an installment sale to be reported in the year payment is received. The purpose of the installment method of reporting income is to alleviate the hardship on taxpayers who would otherwise recognize the entire gain on a sale, but who did not receive sufficient cash to pay the tax. Under the installment method, the tax due is matched with the payments to be received, rather than forcing the taxpayer to advance the tax payments prior to actually receiving the sale proceeds.

Section 453(e) generally limits the use of the installment sale method in the case of second dispositions by related parties. Section 453(e) provides in pertinent part as follows:

Section 453(e). SECOND DISPOSITIONS BY RELATED PERSONS.

(1) In General. – If

(A) Any person disposes of property to a related person, and

(B) before the person making the first disposition receives all payments with respect to such disposition, the related person disposes of the property, then, for purposes of this Section, the amount realized with respect to such second disposition shall be treated as received at the time of the second disposition by the person making the first disposition.

Section 453(f) allows installment sale treatment between related persons if the entrepreneur did not have as one of his principal purposes the avoidance of tax.

The term “related person” is determined by reference to Section 453(f). Section 453(f) provides that for purposes of Section 453, the term related person means a person whose stock would be attributed under Section 318(a) or Section 267(b) to the person first disposing of the property.

Section 318(a)

“Related person” means a person whose stock would be attributed under Section 318(a) to the person first disposing of the property.

Section 318(a)(1)(A) provides that an individual is attributed the stock owned by his or her spouse, children, grandchildren, and parents.

The upward attribution rules (i.e., attribution from an Corporation up to its owners) are found in Section 318(a)(2). Stock owned by a partnership is deemed to be owned by its partners. Stock owned by a trust is deemed to be owned by its beneficiaries and its grantor. Stock owned by a corporation is deemed to be owned by its shareholders, but only if such shareholder owns at least 50% of the corporation.

The downward attribution rules (i.e., attribution from an owner down to an Corporation) are found in Section 318(a)(3). A partnership is deemed to own any stock owned by its partners. A trust is deemed to own any stock owned by its beneficiaries or its grantor. A corporation is deemed to own any stock owned by its shareholders, but only if such shareholder owns at least 50% of the corporation.

Section 267(b)

“Related person” means a person who bears a relationship described in Section 267(b) to the person first disposing of the property:

- Members of a family (siblings, spouse, ancestors, and lineal descendants);

- An individual and a corporation if such individual owns more than 50 percent of such corporation.

- A grantor and a fiduciary of a trust;

- A fiduciary of a trust and a fiduciary of another trust, if the same person is a grantor of both trusts;

- A fiduciary of a trust and a beneficiary of such trust;

- A fiduciary of a trust and a beneficiary of another trust, if the same person is a grantor of both trusts;

- A fiduciary of a trust and a corporation more than 50 percent in value of the outstanding stock of which is owned, directly or indirectly, by or for the trust or by or for a person who is a grantor of the trust;

- A person and an organization to which Section 501 (relating to certain educational and charitable organizations which are exempt from tax) applies and which is controlled directly or indirectly by such person or (if such person is an individual) by members of the family of such individual;

- A corporation and a partnership if the same persons own— more than 50 percent in value of the outstanding stock of the corporation, and more than 50 percent of the capital interest, or the profits interest, in the partnership;

- An S corporation and another S corporation if the same persons own more than 50 percent in value of the outstanding stock of each corporation; or

- An S corporation and a C corporation, if the same persons own more than 50 percent in value of the outstanding stock of each corporation.

Summary of Section 453(e)

Section 453(e) disallows installment sale treatment where there is a disposition of property to a related person (“first disposition”) and, before all payments have been made for the first disposition, the related person disposes of the property (“second disposition”).

Section 453(e) does not disallow installment sale treatment where the first disposition is to a party that is not a related person.

Section 453(f) allows installment sale treatment between related persons if the entrepreneur did not have as one of his principal purposes the avoidance of tax.

Substance Over Form Doctrine

In Gregory v. Helvering, a case from 1935, the court held that where a transaction has no substantial business purpose other than the avoidance or reduction of Federal tax, the tax law will not respect the transaction. The doctrine of substance over form is essentially that, for Federal tax purposes, a taxpayer is bound by the economic substance of a transaction where the economic substance varies from its legal form.

The concept of the substance over form doctrine is that the tax results of an arrangement are better determined based on the underlying substance rather than an evaluation of the mere formal steps by which the arrangement was undertaken. Under this doctrine, two transactions that achieve the same underlying result should not be taxed differently simply because they are achieved through different legal steps. As stated by the Supreme Court, a “given result at the end of a straight path is not made a different result because reached by following a devious path.”

The application of the substance over form doctrine is highly factual. In Newman v. Commissioner, the Second Circuit, indicated that relevant criteria in applying the substance over form doctrine included:

1) the existence of a legitimate non-tax business purpose;

2) whether the transaction has changed the economic interests of the parties;

3) whether the parties dealt with each other at arm’s length; and

4) whether the parties disregarded their own form.

If the doctrine applies, it allows the Service to recast the transaction in question according to the underlying substance of the transaction rather than being bound by the taxpayer’s form. However, taxpayers are typically bound by their chosen legal form.

Step Transaction Doctrine

The step transaction doctrine is considered an extension of the substance over form doctrine. Under the step transaction doctrine, a particular step in a transaction can be disregarded for tax purposes if the taxpayer could have achieved its objective more directly, but instead included the step for no purpose other than to avoid tax. The step transaction doctrine applies in cases where a taxpayer seeks to go from point A to point D and does so by stopping at intermediary points B and C. The purpose of the unnecessary stops is to achieve tax consequences differing from those which a direct path from A to D would have produced. In such a situation, courts may disregard the taxpayer’s path and the unnecessary steps.

The step transaction doctrine “treats a series of formally separate ‘steps’ as a single transaction if such steps are in substance integrated, interdependent, and focused toward a particular result.” The courts have developed three tests to decide whether to invoke the step transaction doctrine:

1) the end result test;

2) the interdependence test; and

3) the binding commitment test.

The end result test is the broadest of the three methods. The end result test evaluates whether it is evident that each of a series of steps is undertaken for the purpose of achieving the ultimate result.

The interdependence test requires showing that each step was so interdependent that the completion of an individual step would have been meaningless without the completion of the remaining steps. Stated differently, under the interdependence test, the step transaction doctrine applies if “the steps are so interdependent that the legal relations created by one transaction would have been fruitless without a completion of the series.”

The binding commitment test is the narrowest of the three step transaction methods and looks to whether, at the time the first step is entered into, there is a legally binding commitment to complete the remaining steps.

In determining whether to invoke the step transaction doctrine, the courts have looked to two factors: (1) the intent of the taxpayer, and (2) the temporal proximity of the separate steps. Excluding cases involving a legally binding agreement, if each of a series of steps has independent economic significance, the transactions should not be stepped together. In addition, the courts have refused to apply the step transaction doctrine where its application would create steps that never actually occurred. If the doctrine does apply, then the unnecessary steps are disregarded, and the transaction is recast.

Economic Substance Doctrine

The economic substance doctrine is considered an extension of the substance over form doctrine. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit applies the economic substance doctrine to determine if a transaction was a sham that should be disregarded for tax purposes. In determining whether a transaction is a sham that lacks economic substance, the Ninth Circuit applies a two-pronged analysis considering:

1) whether the taxpayer has demonstrated a non-tax business purpose for the transaction (a subjective analysis); and

2) whether the taxpayer has shown that the transaction had economic substance beyond the creation of tax benefits (an objective analysis).

The Ninth Circuit has held that this test is not a “‘rigid two-step analysis,’ but rather a single inquiry into ‘whether the transaction had any practical economic effects other than tax benefits.’

Analysis

As discussed above, Prior to 1980, the Service relied upon the doctrine of substance over form when attacking the legitimacy of related party installment sale transactions. The related party installment sale transactions in Rushing, Weaver, Pityo and Roberts all survived the substance over form doctrine.

In Rushing, the court ruled in favor of the taxpayers, explaining that “the trustee was independent of the taxpayer’s control” and had “independent duties and responsibilities to persons other than the taxpayers.”

In Weaver, the Service attacked this arrangement on lack of economic reality and substance over form. In a detailed opinion, the court rejected all of these arguments and held for the taxpayer. The decision in Weaver rests squarely on the two-part, control or economic benefit test of Rushing. The court observed that in Rushing the sale had economic substance because the trustee had the power to void the plan of liquidation.

In Pityo, the court experienced little difficulty concluding that the trustee’s independence, the economic risk it bore with respect to corpus appreciation or depreciation, and its fiduciary duties to the trust beneficiaries created numerous substantive purposes for the structure of the transaction both from the perspective of the trust as well as the taxpayer.

In Roberts, the Ninth Circuit found in favor of the taxpayer, explaining that the irrevocable trust was not a “mere conduit” for the taxpayer. The Ninth Circuit further explained that the taxpayer had “no control over the trust or the trustees” and “had actually and effectively foregone the benefits [of the stock sales], electing instead to receive the use and enjoyment of the installment proceeds.”

Installment Method

The installment method is used for reporting gains (but not losses) from an installment sale, which is a sale involving a disposition of property where at least one payment is received by the seller after the tax year in which the disposition occurs.

The installment method applies even if only one payment is to be received, as long as that payment is received in a tax year following the year of sale. It also applies without regard to the timing of the transfer of title (e.g., even if the transfer of title will not occur until all of the agreed-upon selling price has been paid).

The installment method may apply to the sale of a single asset, the sale of several assets in a single transaction, or the sale of a business. However, use of the installment method is prohibited with respect to the following transactions and types of gain (among others):

- Sales made by a dealer (Section 453(b)(2)(A))

- Sales of inventory related to personal property (Section 453(b)(2)(B))

- Sales of depreciable property to a related person (Section 453(g))

- Sales of personal property under a revolving credit plan (Section 453(k)(1))

- Sales of publicly-traded property (Section 453(k)(2))

- Gain attributable to depreciation recapture (Section 453(i))

Practice Tip: While the installment method of reporting affects the year in which gain is recognized, it does not affect the character of the gain.

The gain reported in any given year under the installment method is equal to the total payments received during the year (other than interest) multiplied by the ‘gross profit percentage.

Calculations in the year of sale

In the year an installment sale occurs, several calculations must be made in order to arrive at the gross profit percentage.

Selling price — The selling price is the total consideration received by the seller for the sale of the property, including money, the FMV of property, and debt (such as a mortgage on the property) assumed by the buyer. Interest (whether stated or imputed) is not considered part of the selling price.

Adjusted basis — The seller’s adjusted basis in the property sold is determined according to the rules outlined in Sections 1011, 1012, and 1016. Although the rules for calculating adjusted basis can be complex, adjusted basis generally is determined by taking the seller’s original cost of the property, then increasing it for any improvements or additions and decreasing it for any depreciation or amortization. Basis also is adjusted for selling expenses paid by the seller.

Gross profit — The gross profit is the selling price less the seller’s adjusted basis in the property sold (i.e., the expected gain on the sale).

Total contract price — The total contract price is the selling price less any qualified indebtedness assumed by the buyer (but only to the extent that the debt assumed does not exceed the seller’s basis in the property sold). Qualified indebtedness for this purpose means a mortgage or other indebtedness encumbering the property, and indebtedness not secured by the property but incurred or assumed by the purchaser incident to the purchaser’s acquisition, holding, or operation of the property.

Gross profit percentage — The gross profit percentage is the ratio of the gross profit to the total contract price.

Calculations each year payment is received

For each payment received in connection with an installment sale, the seller must determine the correct amount of gain, return of basis, and interest.

Gain — Gain is calculated each year by multiplying the gross profit percentage on the sale by the total value of the installment payments (other than interest) received during the year. The amount of gain calculated each year is reported on the taxpayer’s return as the amount of taxable gain for the current year.

Return of basis — Any amount of the payment remaining after gain has been accounted for is considered a return of the seller’s basis, which is non-taxable.

Interest received in addition to principal is accounted for as ordinary income to the seller.

General reporting requirements

Installment sales are reported on Form 6252, Installment Sale Income. This form must be completed and attached to the taxpayer’s return in any year that property is sold in a qualifying installment sale and in any year that the taxpayer receives a payment from an installment sale, assuming the taxpayer did not choose to elect out of the installment method.

Criteria

1. Did the seller report gain from the sale of property under the Section 453 installment method of accounting?

a.The seller must report gain from the sale of property under the installment method for Section 453A to be applicable.

b.The seller uses a separate Form 6252 for each installment sale or other disposition of property on the installment method.

2.Did the sales price of the property exceed $150,000?

a.The sales price of the property must exceed $150,000 for Section 453A to be applicable.

b.Review the Form 6252 to identify an installment sale with a sales price exceeding $150,000.

c.In determining the sales price, treat all sales that are part of the same transaction (or series of related transactions) as one sale.

3.Is the installment obligation to which Section 453A applies outstanding as of the close of the taxable year?

a.The obligation must be outstanding as of the close of the taxable year for Section 453A to apply.

4.Did the face amount of all installment obligations to which Section 453A applies, that arose during and were outstanding as of the close of that taxable year, exceed $5 million?

a.Section 453A is only applicable when the face amount of all installment obligations that arose during and outstanding as of the close of that taxable year exceeds $5 million.

Recommendations

- Consider Section 453A when analyzing installment sale transactions and advise clients of the interest charge, which is an additional economic cost of entering into the installment obligation.

- In Technical Advice Memorandum 9853002, the IRS ruled that married individuals are not treated as one person in calculating the $5 million threshold. Since each spouse will receive his or her own $5 million threshold in the calculation of the interest charge, a gift of the target property from one spouse to another effectively doubles the threshold amount.

Interest on Deferred Tax Liability

Section 453A imposes an interest charge to a disposition of property under the installment method when the sales price of the property exceeds $150,000 (the “453A Obligation”).

Interest is imposed on a 453A Obligation arising during a taxable year only if (1) the obligation is outstanding as of the close of the taxable year, and (2) the face amount of all 453A Obligations held by the seller that arose during, and are outstanding as of the close of, that taxable year exceeds $5 million.

Section 453A(c)(1) provides that the taxpayer’s income tax is increased by the interest charge. The interest charge is reported on the taxpayer’s Form 1040, U.S. Individual Income Tax Return.

The $5 million threshold is applied and calculated at the partner or shareholder level for all passthrough entities.

Section 453A(c)(5) further states that any amount paid under this section is taken into account in computing the amount of the taxpayer’s interest deduction for the tax year. The interest is subject to the rules that dictate whether interest incurred on tax underpayments is deductible by the taxpayer. A number of court cases, as well as Section 163 and related Temp. Regs. Sec. 1.163-9T(b)(2)(i)(A), take the position that interest on an individual underpayment of federal income tax is nondeductible personal interest regardless of whether the tax liability is from a business or investment activity.

Therefore, for individual taxpayers, the Section 453A interest charge is considered nondeductible personal interest. But C corporations are allowed to deduct the interest charge as a business expense in most circumstances in the year paid or accrued because C corporations are not subject to the limitations on deductions for personal interest expense.

Monetized Installment Sales

- Monetized Installment Sales. These transactions involve the inappropriate use of the installment sale rules under section 453 by a seller who, in the year of a sale of property, effectively receives the sales proceeds through purported loans. In a typical transaction, the seller enters into a contract to sell appreciated property to a buyer for cash and then purports to sell the same property to an intermediary in return for an installment note. The intermediary then purports to sell the property to the buyer and receives the cash purchase price. Through a series of related steps, the seller receives an amount equivalent to the sales price, less various transactional fees, in the form of a purported loan that is nonrecourse and unsecured.

- On July 1, 2021, Monetized Installment Sales were listed on the IRS “Dirty Dozen” list, which is the publication the IRS uses to alert the public of abusive transactions.

- The IRS issued proposed regulations on August 4, 2023 (the “Proposed Regulations”). The Proposed Regulations, if finalized, would require taxpayers and material advisors who participated in Monetized Installment Sales to disclose their participation to the IRS. Generally, taxpayers who entered into Monetized Installment Sales would be required to file Form 8886, Reportable Transaction Disclosure Statement.

Deferred Sales Trust vs. Monetized Installment Sale

Deferred Sales Trust transactions are NOT Monetized Installment Sales transactions because the seller does not receive an amount equal to the sales price in the form of a purported loan.

The information provided is for informational purposes only and does not constitute tax or legal advice. Please consult a qualified professional regarding your specific circumstances.